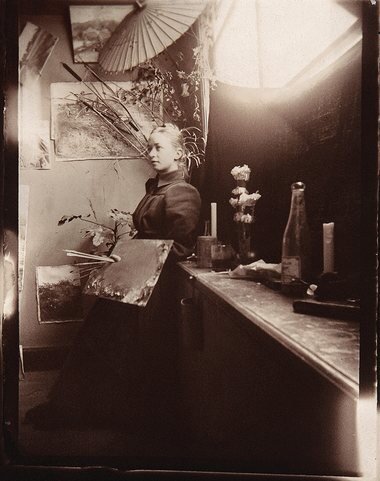

Agnes Martin

'Our lives are broader than we think'.

The best works in this show at Tate Modern posess a luminous beauty to be carried away and returned to whenever there is a need for space to think.

Untitled 1998.

Sonia Delaunay

The Russian born artist showing at Tate Modern made paintings, fashion and textiles.

Matisse: "Looking at Life with the Eyes of a Child"

Creation is the artist’s true function; where there is no creation there is no art. But it would be a mistake to ascribe this creative power to an inborn talent. In art, the genuine creator is not just a gifted being, but a man who has succeeded in arranging for their appointed end a complex of activities, of which the work of art is the outcome.

Thus, for the artist creation begins with vision. To see is itself a creative operation, requiring an effort. Everything that we see in our daily life is more or less distorted by acquired habits, and this is perhaps more evident in an age like ours when the cinema posters and magazines present us every day with a flood of ready-made images which are to the eye what the prejudices are to the mind.

The effort needed to see things without distortion takes something very like courage; and this courage is essential to the artist, who has to look at everything as though he saw it for the first time: he has to look at life as he did when he was a child and, if he loses that faculty, he cannot express himself in an original, that is, a personal way.

To take an example: Nothing, I think, is more difficult for a true painter than to paint a rose because, before he can do so, he has first to forget all the roses that were ever painted. I have often asked visitors who came to see me at Vence whether they had noticed the thistles by the side of the road. Nobody had seen them; they would all have recognised the leaf of an acanthus on a Corinthian capital, but the memory of the capital prevented them from seeing the thistle in nature. The first step towards creation is to see everything as it really is, and that demands a constant effort. To create is to express what we have within ourselves. Every creative effort comes from within. We have also to nourish our feeling, and we can do so only with materials derived from the world about us. This is the process whereby the artist incorporates and gradually assimilates the external world within himself, until the object of his drawing has become like a part of his being, until he has it within him and can project it on to the canvas as his own creation.

When I paint a portrait, I come back again and again to my sketch, and every time it is a new portrait that I am painting: not one that I am improving, but a quite different one that I am beginning over again; and every time I extract from the same person a different being. In order to make my study more complete I have often had recourse to photographs of the same person at different ages; the final portrait may show that person younger or under a different aspect from that which he or she presents at the time of sitting, and the reason is that that is the aspect which seemed to me the truest, the one which revealed most of the sitter’s real personality.

Thus a work of art is the climax of a long work of preparation. The artist takes from his surroundings everything that can nourish his internal vision, either directly, when the object he is drawing is to appear in his composition, or by analogy. In this way he puts himself into a position where he can create. He enriches himself internally with all the forms he has mastered and which he will one day set to a new rhythm.

It is in the expression of this rhythm that the artist’s work becomes really creative. To achieve it, he will have to sift rather than accumulate details, selecting, for example, from all possible combinations, the line that expresses most and gives life to the drawing; he will have to seek the equivalent terms by which the facts of nature are transposed into art.

In my Still Life with Magnolia, I painted a green marble table red; in another place I had to use black to suggest the reflection of the sun on the sea; all these transpositions were not in the least matters of chance or whim, but were the result of a series of investigations, following which these colours seemed to me to be necessary, because of their relation to the rest of the composition, in order to give the impression I wanted. Colours and lines are forces, and the secret of creation lies in the play and balance of those forces.

In the chapel at Vence, which is the outcome of earlier researches of mine, I have tried to achieve that balance of forces; the blues, greens and yellows of the windows compose a light within the chapel, which is not strictly any of the colours used, but is the living product of their mutual blending; this light made up of colours is intended to play upon the white and black-stencilled surface of the wall facing the windows, on which the lines are purposely set wide apart. The contrast allows me to give the light its maximum vitalising value, to make it the essential element, colouring, warming and animating the whole structure, to which it is desired to give an impression of boundless space despite its small dimensions. Throughout the chapel every line and every detail contributes to that impression.

That is the sense, so it seems to me, in which art may be said to imitate nature, namely, by the life that the creative worker infuses into the work of art. The work will then appear as fertile and as possessed of the same power to thrill, the same resplendent beauty as we find in works of nature.

Great love is needed to achieve this effect, a love capable of inspiring and sustaining that patient striving towards truth, that glowing warmth and that analytic profundity that accompany the birth of any work of art. But is not love the origin of all creation?

Henri Matisse

February 1954 Art News and Review

Alexander Calder at Pace Gallery, London

I recommend the glorious works of sculptor Alexander Calder who came from three generations of artists and trained originally as an engineer. His mobiles and stabiles from the mid forties are the exceptional jewels amongst his work. They are mesmerising conversations with Nature, humble and powerful in their economy, making visible the forces at play.

Nitrogen

The excited energy states of the nitrogen nucleus.