I’m thumbing through the newspapers by the coffee bar in the senior common room when you pop up, your back-pack in your hand, like you’ve just got off your bicycle. Though I don’t realise it at first, you are the first political scientist I have met. And you are the first woman to tell me about her work. We sit down with coffee and tea either side of the table, you buzzing with energy.

You tell me that you are finding the rules and the right materials to make good performing solar cells out of cheaply processed materials. These are conducting polymers. It is not hard to excite the electrons with the sun’s light; the challenge is to get the energy out efficiently, how to get the electron to travel and not just de-excite releasing more light. So you add the wonderful sounding fullerene.

You have around twelve people (people are always coming and going), half who test new materials and the rest who model and design them, which may involve for example solving Schrodinger’s Equation for new materials to find the energy levels. And you work closely with people from other departments like Chemistry, Materials and Chemical Engineering.

Traditional solar cell materials won’t go away you say, clicking your gallium nitride bike lamp on and off, but these new materials will play a complementary role. We cast our eyes towards the expansive common room window, the blinds could be solar cells and these thin sun catching layers could be laid across the roofs of supermarkets. We reflect on how the supermarkets would still probably consume more that the sun’s generous provision. I think how these ideas could transform the world and you point out that we need to figure out how to manage all these high currents that would stream off everything.

You have left physics three times. After your Cambridge degree you worked for the Greater London Council introducing technology within the community. Then after a PhD at Bristol where you simulated the way soot particles absorb light to understand how we would be affected by nuclear winter, (the US Government said autumn, but your research said winter). You left physics again and did some volunteering, some of it political. Then you hooked up with Keith Barnham who re-educated himself switching from particle physics to solar energy, one of the first into this field. When you started, almost no one did this in the UK.

And you are well known and a leader in your field (you don’t tell me, I guess and ask). And after our conversation, when I mention you to others they say you are ‘amazing’.

You also work for the Grantham Institute of Climate Change looking at the role of technology and helping to understand potential contributions. ‘Imperial College is slightly anarchic; researchers are allowed to do more or less what they want'. That is the way to keep happy academics. But, you work in a deep way and organise and pull people in.

After stopping off in your cheerful corner office where it is breezy with high up views over London, we leave the travel books and sports gear behind to visit the labs.

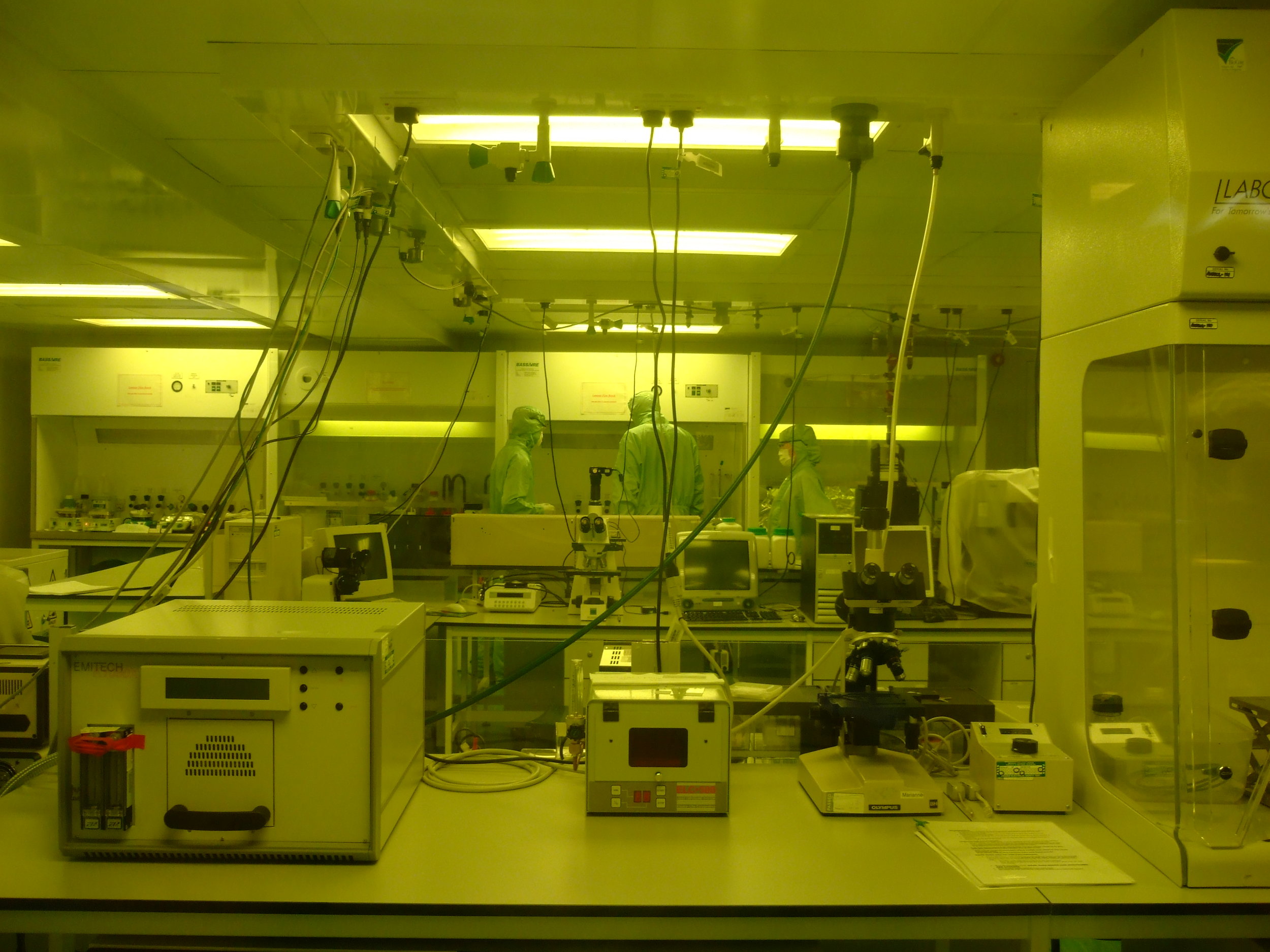

Some are clean labs with carefully controlled environments: minimal particles and moisture and with ultra violet removed from the lights, so the air is tinged with yellow. Peering through the window the figures moving silently around behind the glass panel are clad anonymously in pale mint suits from head to toe. They are making photovoltaic surfaces. In another room, also lit yellow is the hilarious glove box, six black rubber supersized arms reaching towards us, puffed out with nitrogen.

And we go on to see spaces where the fabulously named ‘flight times’ (of electrons) are measured and the spectral absorption of materials. It is careful and delicate work, making catchers for sunlight.

You ask out loud what influences made you political? Your mum is a chemist (in fact both your parents were chemists) who helped set up the first Open University courses and was one of the first to teach science degrees in prisons. Maybe it was that, or maybe it was growing up in Belfast during the troubles, or maybe it was just the 80’s. When you were 11, your history teacher decided you were political.

‘It’s important to know why you’re solving problems’ you say. ‘Solar energy is a great motivation. The sun can’t be owned, and if we can make solar power more widely available, people can control their own lives better and have better lives.’

Jenny Nelson works on making new materials for capturing the sun's energy. She also travels the world and cycles, swims and runs......She believes in free access to the sun for everyone.